Forestry Commission - Inverness

Smithton

Project Status

Completed

Project Sector

Commercial

Client

Forestry Commission Scotland

Contractor

M.M. Miller Ltd

Surveyor

Armour & Partners

Engineer

Fairhurst

M&E Engineer

Pick Everard

Location

Inverness

Boldly going where no one had gone before...

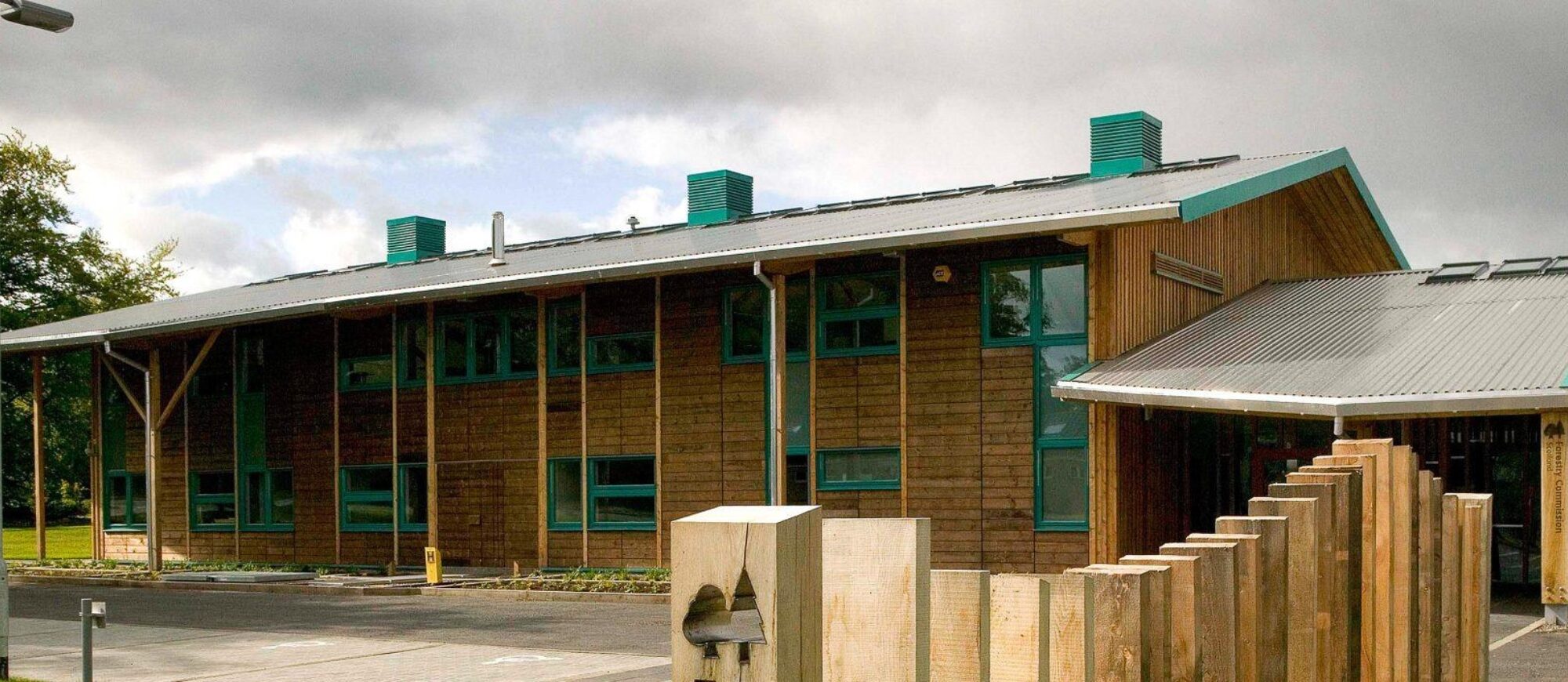

The subject of sustainability in the construction industry was in its infancy in 2005. Buzzwords such as ‘sustainability’ and ‘carbon footprint’ were being used, but the definition was sparse other than the cumbersome and prescriptive BREEAM process, and very much open to interpretation. This project had these requirements at its core and once appointed we proposed that we take a clean sheet approach to the subject looking carefully at how sustainability could be best adopted in this particular situation.

We started with the client; the Forestry Commission, caretaker of the nation’s forests. The Forestry Commission have a diverse portfolio and at the time of this project, much of the local focus was on woodlands and forestry as leisure opportunities rather than timber production for the construction industry. At the same time, the government was exploring the idea that their plantations could have an ‘added value’ element if suitable for the construction market.

The vast majority of the timber used in the UK construction industry is imported, and there was a presumption that UK timber was inferior and generally unavailable. Working with Napier University, we had local timber tested for strength, and graded and discovered that the timber was of a significantly higher quality than anyone expected. The problem was lack of volume, and lack of infrastructure to extract and process what was available. This new knowledge allowed us to consider using locally grown Douglas Fir as the primary structure.

Our objectives soon developed around the idea that we could use locally grown timber from within 50 miles of the site for the structure, the framing, the external timber cladding, the flooring and some of the bespoke joinery items such as screens. This approach satisfied two aims; reducing road miles and demonstrating what could be done with local products.

Timber cladding from homegrown sources was also misunderstood. The timber import industry had effectively dispelled any idea that homegrown timber could be used for cladding due to durability issues. We looked at emerging and in some cases older timber modification processes to see what could be done to bring Scottish European larch and Scots pine into the cladding market. We discovered the furfurylation process. This industrial alcohol-based process modifies timber to make it extremely durable and resistant to beetle and worm attacks. The use of this allowed us to use Scots Pine from Culben Forest at the main cladding for the building. The warm dark chocolate effect interspersed by larch and Douglas fir was used in a pleasing way to define the structure elevationally and break up the mass.

Homegrown European larch if carefully selected and detailed correctly is sufficiently durable in the Scottish climate. The issue was technique. To some extent we had lost the art of using timber externally so we looked at how the Norwegians use timber successfully in a similar climate on their Atlantic coast. Timber can be wetted regularly but provided the water can escape easily and dried quickly afterwards is durable for many years. Protecting the timber from water in the first place is beneficial so we used a large oversailing roof plate to give shelter from the rain.

For the floors and wall panels we were keen to achieve high levels of insulation using mineral wool rather than PIR insulation for environmental reasons. A simple way to reduce the ‘cool-bridging’ of the fabric through the timber framing was to use ‘I’ joists. These were manufactured nearby at the James Jones & Sons factory in Forres. Called the JJI-joist, these were commonly used as lightweight floor joists. We wondered if there was any reason why these could not be stood on end and used as studs. Apparently not, so we worked with the engineers and the supplier to develop this idea. This had a 9% thermal improvement across the wall panels.

Internally, we used Scottish-grown European oak for the flooring and finishes, some of which was left over from the Scottish Parliament building. This was dried and milled locally. We also used the leftover Douglas Fir for framing to the glazed screens; a focus on efficiency in this bespoke design.

This building proved to be ground-breaking. As well as gaining a BREEAM ‘Very Good’ score it won the 2008 RICS ‘Most Sustainable Building in Scotland Award’ and won in the 2008 IAA design awards. But more importantly, it was recognised as being the first commercial-scale building in the UK to use exclusively homegrown timber, dispelling the myths and opening the sector for the future. The building features in the publication ‘New Timber Architecture in Scotland’ by Peter Wilson, and our research has featured in several timber design and use guides. This project redefined our focus towards our main objective of ‘pragmatic sustainability’ in the design of our buildings.